When I first came across Kip Rasmussen’s work, I knew it was exceptional, and that I’d probably like everything he made. His paintings present all the best components of high fantasy: long hair flowing from beneath helms, brazen swords, gleaming spears, fire-breathing dragons, primordial godlike beings, imposing pinnacles of rock, and an insanely huge spider. Yup—these were scenes right out of J.R.R. Tolkien’s legendarium, instantly recognizable as features of Middle-earth. But curiously, only a few of them depict characters in The Lord of the Rings itself. Here was a Silmarillion-leaning artist. Oh, hell yeah.

When I contacted Kip to ask permission to use some of his work in my Silmarillion Primer, he just happened to be mulling over three ideas in his mental queue and he was quick to ask me to choose which subject he’d tackle next. I chose “Tulkas Chaining Morgoth,” so when he finished it later, it was right on time for the War of Wrath segment of the Primer. That made me very happy. And now, once again, I’m debuting a new painting in this article: Kip’s take on that legendary conflict between a certain lionhearted shield-maiden and a certain overconfident lord of carrion.

As soon as I realized I wanted to interview some of my favorite Tolkien artists, I knew Kip Rasmussen would be on the list. Not just because some of his paintings would make awesome Led Zeppelin album covers—or frankly, any prog rock album since the 70s—but because he’s a down-to-earth human being who’s more than meets the eye.

So let’s get right to it.

Kip, can you tell me, in a nutshell, how you fell into Tolkien’s mythologies? At what age did you first encounter his work, and at what age did you actually sink in deep beyond the point of no return?

Kip: At age 8, I found The Hobbit on my brother’s bookshelf, opened it, and that was it right there. I couldn’t believe what I had found. I still can’t believe it. I moved right into The Lord of the Rings and the free fall continued. I remember sitting in class in fourth grade reading the Moria passage, stressing out visibly. A classmate looked over and said, “What’s wrong?” I barely looked up and lamented, “Gandalf just died!” Poor kid looked very confused.

Obviously this was before Gandalf became a household name, because of the films. (Though arguably, he already was a name in some households, but that’s another story.)

Now, I know you as a kick-ass painter who favors Tolkien above all. But you’re also an author and film producer? Can you tell me about that?

Kip: I work with the filmmaker Tom Durham. We met at a party and found we shared a love of science fiction and fantasy. He directs the films and I help him with a bunch of tasks involved in independent films—help with story ideas, concept art, props, fundraising, etc. His first feature is 95ers: Time Runners, which is a time travel thriller. He is now involved in a wonderful local television show which tells the story of the ups and downs of the lives of everyday people. Kind of the idea that everyone has a story to tell. Our goal is to move into a multi-season science fiction or fantasy series such as can be found on channels nearly everywhere. He is a tremendously talented artist with infinite energy.

Nice! And hey, my brother’s got the DVD, even backed the Kickstarter for that film. And yeah, you have an IMDB page, don’t you? Keep growing that! But you’re also a therapist, too, right?

Kip: Yes. My day job is as a family therapist and I have published a book on parenting. I took what forty years of research has revealed about the most effective parenting elements and derived easily usable tips from that body of research. The cool thing is that, because of that research, we don’t really have to guess much anymore. In a nutshell, the most effective parenting involves a lot of love and support coupled with some reasonable rules applied as gently as possible to get the job done. We don’t have to yell or punish in the traditional sense. We just have to make sure we lean enough that kids follow the rules that will help them be successful in their lives without triggering their natural impulse to be defiant against us. It’s been very helpful with my own kids and the kids of my clients.

What do you mean by lean?

Kip: I use the comparison of the “weight of the leaning elephant” rather than a charging, trampling, or goring elephant. Kids are awesome and if we are just insistent and “lean” on them when they need correcting, the research shows that we get better long-term results. If we yell, we generally get short-term compliance, but we also show them that we are out of control and they tend to not trust us as much. Most of us hate being bossed around and kids are very prone to defiance if they feel we are abusing our authority. This all hits the fan when they turn 13 or 14.

I’m officially bookmarking this article to refer back to in a few years, in that case! Thanks. So before I circle back to Tolkien specifically, what’s your authorship status?

Kip: I am expanding a novella about two warriors who venture into a mountain fastness to try to kill a dragon-like creature which has been terrorizing their city. They don’t expect to live long but what they find is much worse than they foresaw. It’s fun to build a world, something which yet again shows me how astonishing Tolkien’s genius was.

I know, it’s downright intimidating—that is, doing your own world-building when you’re a Tolkien fan. But it’s still worth doing. Like that time when Morgoth, the first Dark Lord of Middle-earth wanted to destroy the Two Trees of Valinor but needed the help of the hideously powerful, light-craving Ungoliant. He had to work out an agreement with her, and she was difficult, and it didn’t ultimately go swimmingly for him. Say, you painted that outcome…

But it was worth it in the long run, is my point. He did manage to destroy the Trees, sow chaos in Valinor, and make off with those shiny Silmarils. Likewise, it’s a lot of extra work to devise your own setting in the shadow of what Tolkien did—but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try.

So, I would say that most casual fans of Tolkien understandably extol and reread The Lord of the Rings or The Hobbit. A smaller percentage, from what I can tell, really know The Silmarillion well or have even read it. But even a quick look at your website’s gallery reveals that, in fact, most of your work is based on that book. You’ve called it more “fundamental” than his other books, and “one of the most preeminent works of art ever created.” And I certainly agree! Can you elaborate, or give any specific examples of why you think so? Do you find it a more enjoyable read, page by page?

Kip: All of Tolkien’s work has its glory. Unfinished Tales is probably my second favorite book. But The Silmarillion is just so infinite and transcendent. It takes everything we love about The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings and gives us exponentially more. More gods, Elves, Balrogs, dragons, battles, marvelous cities and dwellings, love stories, and origin stories. If we want to learn about where everything comes from, from Elves to stars, from Ents to Orcs, it’s there. Tolkien forgot almost nothing. The origin story of Dwarves and Ents is particularly fascinating because it involves a fundamental disagreement about the nature of the world from a couple of married gods! Also, could there be anything more riveting than the story of Beren and Lúthien, in which a woman saves her love from death several times, eventually literally from the God of the Underworld himself…by singing of her eternal love? So many, many timeless themes, from our relationship to authority and God (Morgoth, Ulmo, and Fëanor), to the nature of sacrifice and suffering (Barahir and Finrod), to the self-destructive pride of the most talented among us (Fëanor, Turgon, Túrin, Thingol) to the necessity of reigning in our darkness (Maeglin, Ar-Pharazôn).

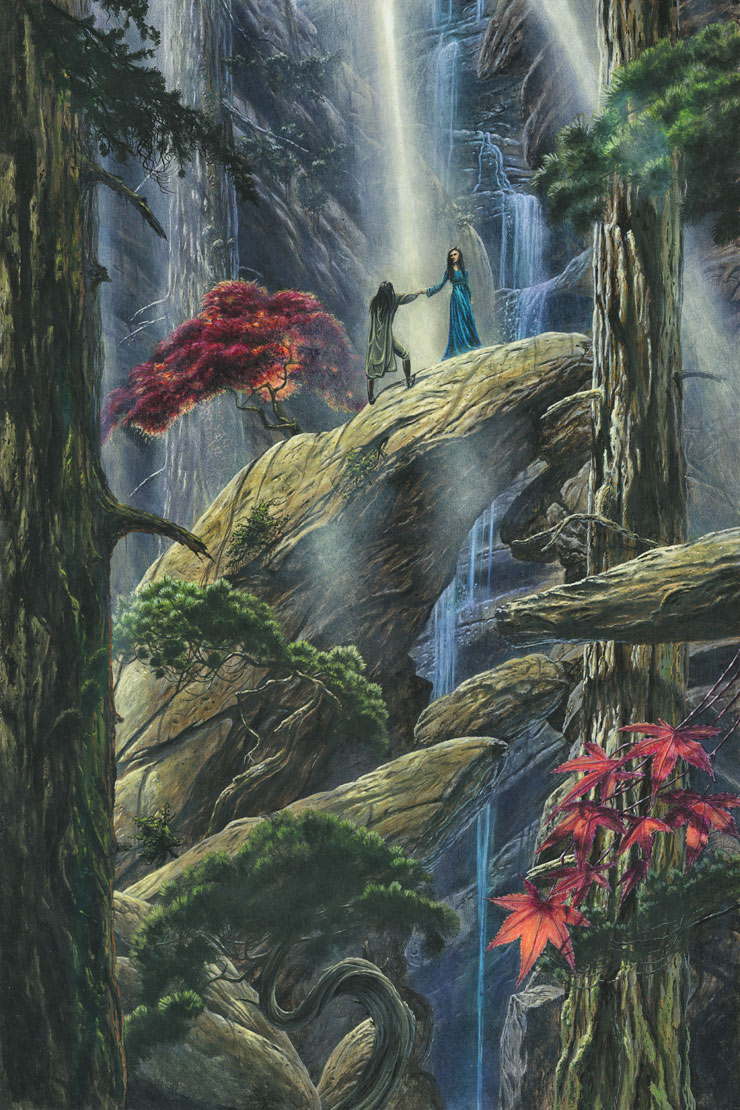

Well, you get points just for name-dropping Finrod. But maybe that’s just me. Oh, and speaking of Thingol, you illustrated his famous meeting with the songbird-themed Maia, Melian, in the forest of Nan Elmoth. This is easily one of my favorites. I’ll share that one further down.

Anyway, go on.

Kip: The Silmarillion is not just one of the greatest works of serious world literature, but one of the greatest achievements in all of artistic endeavor. For me, it is by far the greatest work by the most expansive single creative mind of all time. Other than the really important things such as family, etc., my most cherished dream in life is to introduce this magnificent creative achievement to those who might appreciate it. But it can be a locked treasure trove because of all the new names. It took three times reading it for me to understand what was happening. But if people can be helped through images to get through all the new names, I hope it can lift them like it has me.

Only three? Good on you! But yeah, you’re certainly right. If anyone asks me what my favorite single book of all time is, I dodge around The Lord of the Rings using the flimsy three-book excuse (because of course it isn’t three separate books in the author’s mind) and so now I just say The Silmarillion.

I’ve noticed there’s a fascinating sort of “zoomed in” style in your works, in contrast to other Tolkien artists, where it’s clearly focused on an individual, monster, or scene, and yet the landscape is stretched out behind them in a very…stretchy way, if that makes sense? Almost like you’ve got a sort of Ken Burns effect on your paintings at all times. Like with your illustration “Beren and Lúthien Plight Their Troth.” I find myself looking at the figures at the top, then gradually pan down and marvel at the curiously treacherous yet beautiful place they’ve chosen to pledge undying love! It’s cool.

And in “Tuor and Voronwë Seek Gondolin,” you either look first at the jutting mountains and then notice the travelers at the bottom or else you see them first then sweep upward and gape at the frozen challenge ahead of them. How do you do that? Can you talk about your style a little bit?

Kip: What is this new devilry? You are totally reading my artistic mind. It’s a seriously perceptive tribute. Thank you. Tolkien’s world is nearly infinite and The Silmarillion is for me a book in which immortal, meteoric characters are nonetheless caught up in events which overwhelm and consume them. For all the greatness and glory of Fëanor, Melian, Túrin, and Turgon, they are caught in a struggle which is worthy of depiction in all ways, but which they cannot win. The world and the themes are bigger than they are. I love depicting these environments to show the difficulty of the task they have ahead of them. Tolkien’s landscapes can be sinister and malevolent. Mirkwood, the Old Forest, and the Dead Marshes are all enemies which strive to hinder the heroes. I love painting stone, trees, and especially mountains as much as I love warriors and dragons. Tolkien was essentially made of the organic stuff of the earth. The landscapes are often active characters and they deserve their own “portraits.” Caradhras the Cruel, for example, is a living entity and will receive a “close-up” soon. I feel an urgency, a suffocating yearning to depict Middle-earth itself. For me, it’s kind of like the One Ring. I want viewers to be immersed in that marvelous world. This is what moves me so much about the work of Ted Nasmith and Alan Lee. They really breathe the misty, fathomless depths of Arda.

Wow. Well, given how much you’ve personified features of geography—as Tolkien certainly did with “characters” like Caradhras, as you suggest—now I have to ask you my first hypothetical question. If you were one of the Ainur who’d help sing the World into shape (Eä, or at least Arda itself), which named geological feature or landscape would be your favorite? It would be one that, maybe, you’d have had a hand in making? For example, the River Sirion in Beleriand was unquestionably Ulmo’s favorite river of all time (and that guy knew rivers!).

Kip: Probably the water-carved arch of Alqualondë. There are a lot of them I would like to have taken credit for: the Echoriath, the Pelóri , etc. I’m crazy about mountains. I love unusual rock features. I might have some Dwarvish blood :)

Then I think you’d probably be a Maia in service to Aulë. Of course, his Maiar don’t have the best track record…. But it does make sense. Those who worked with Aulë, the Great Smith, are intrinsically crafters and sub-creators. Painters would fit in there nicely.

What sort of paints do you use and why? And do you ever do anything digitally?

Kip: I started out in oils but found that they dry slowly and the clean-up can be messy. I switched to acrylics, which are kind of unforgiving but work for me since I can’t devote full time to painting. I would love to learn the digital world but I am a more organic person. For example, I create Japanese-style gardens and love physically arranging trees, rocks, and dirt. It’s a tactile thing for me. I like physically applying paint rather than drawing on glass. I am about to go back to oils, I think, since I have discovered additives which can help them dry quicker, and that there are alternatives to toxic solvents as well. But oils blend easily and are more luminous. Frankly, I am still learning to paint both artistically and technically. Boris Vallejo once described painting as a dance. For me, it’s a kind of combat. I lose often and even when I produce something to show the world, it’s from a series of compromises with time and skill level. Every painting is a low-key haunting regarding what I originally wanted to do but couldn’t pull off. It’s a blessing and a curse to paint the work of Tolkien. I never want to disappoint Tolkien or Tolkien fans. They deserve the best I can muster up.

Speaking of mustering… Rohan! You’ve recently tackled one of the Rohirrim ancestor-kings, Fram, and his legendary slaying of everybody’s favorite scathing hoarder, the long-worm known as Scatha!

You know, with only a couple of exceptions, I’ve noticed that whenever you’ve got only two characters depicted in a given painting, they’re either falling in love with each other or trying to kill each other. Just an observation.

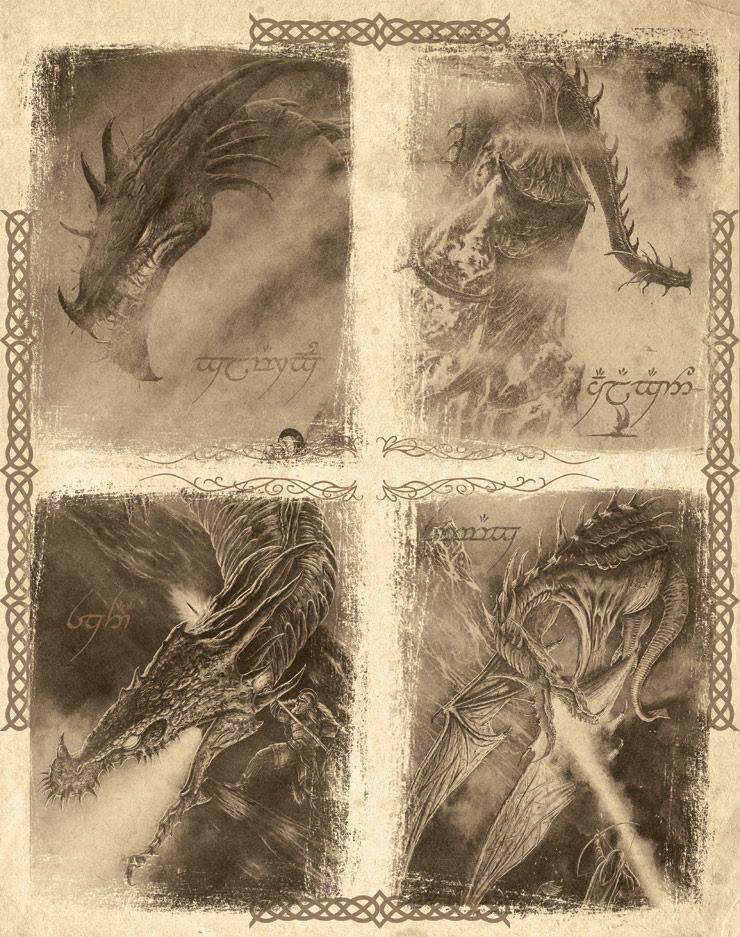

So talk to me about dragons. What sets Tolkien’s apart from all the rest?

Kip: Tolkien’s dragons are not just content to be powerful and destructive, they are also malevolent. Glaurung, for example, wasn’t content to just kill Túrin, but to destroy Túrin’s mind and family. Really disturbing. For me, it’s one of the most tragic stories ever written. Just gut-wrenching. Tolkien’s dragons have a vicious intelligence. One does not simply ride a Tolkien dragon, at least not the organic kind.

So where is a region of Middle-earth—or anywhere in Arda—that you wish Tolkien had fleshed out more? If you got an exclusive description from the hand of the professor himself of one place, character, or scene, where would that be?

Kip: When we describe Tolkien, we should start at genius and then go upward from there. And he spent all of his life building this world. And yet it’s never enough for us. We want more. I wish he had described virtually all lands a little more rather than playing cards. Apparently he loved a form of solitaire called “patience.”

Anyway, I’d love to hear more about Valinor. And the actual structure of Rivendell? Was it the last homely house or a fortress compound as it appears in the war involving Celebrimbor? I know Gondolin was described pretty well, but I’d dearly love an actual map. I want to see Númenor, a nation so magnificent that it astounded Sauron himself.

That’s too many answers! (But they’re all good ones.)

Kip: I’ve struggled to understand how to depict “bright Eärendil.” Was he just so good that he “shone” or was it that he literally glowed? The most curious passage though is how he possibly could have killed Ancalagon while in his ship. That one needs clarification.

Hah! Well, I think the diamond dust dust he kicked up outside of Tirion was a contributing factor. And I think it’s like glitter; once it’s on you, it’s on you for good. Especially Noldorin gem-glitter. But given that by that time he’d already strapped the Silmaril to his brow, the dude was a walking nebula of awesome already. But yes, the chapter starts with him being called “Bright Eärendil.” Still, I think that’s because the narrator is speaking in the past tense; he already knows what Eärendil’s fate will be in the telling.

All right, setting aside all existing films and movie scores, if you had the power to point to a living musician or band of musicians and they had to (let’s say got to) put together an album of Middle-earth music, who would you choose?

Kip: This group is really good: Clamavi De Profundis. Loreena McKennitt has the most marvelously haunted voice. For me this could be Yavanna singing for the trees or Lúthien lamenting the death of Thingol. As for those not living—

Breaking the rules again, I see.

Kip: —there are several. I know these are in Latin and they’re specifically Catholic but they feel so “Elvish” to me. Both kind of fit for Tolkien, though. For example, for me, this piece is the Music of the Ainur. Also, the work of the mighty polymath Hildegard Von Bingen just transports me to Arda. And for those who aren’t overtly religious, here’s one about the plants she wrote about. Like everything in the natural world, Tolkien loved plants, too.

Close enough to my actual question, I guess, you scofflaw. But I dig ’em, and I concur especially that McKennitt could have rendered us some excellent Middle-earth music. Why hasn’t she? Alas.

Okay, back to painting. You’ve just finished this piece, “Éowyn Stands Against the Witch-king.” Now, this is not only the favorite scene of many a Tolkien fan, but it’s also a beloved moment to paint. But every Tolkien artist does it differently, as they should. Some show the Nazgûl’s beast already slain, some have Éowyn delivering that fateful strike. You’ve shown them simply squaring off, the outcome uncertain.

Can you tell me why you chose this particular moment in time, and about your angle?

Kip: I had done a compositional sketch and the gesture of Éowyn was so perfect that I tried to copy it in the larger painting. I was much less successful in doing so but didn’t have the chops to really change it so that it matched the energy and immediacy of the sketch. In the sketch, she was kind of hunkered down bracing for the onslaught. My reference photo looked good in camera but looked too stiff when it was painted. It just happens like that sometimes. That painting really strained my current abilities and took a ton of time. I like it less than some others and want to do another one when I have improved because it’s probably the most iconic scene in Tolkien’s body of work, which is saying something. I just don’t have the energy in my figures that Frazetta does, not that many artists ever have. I do have a nefarious plan to try to get better and better and give the Tolkien work the treatment of Vermeer or Caravaggio. Nothing like pressure!

As far as the moment of the painting, I wanted it to have a bit of “potential” energy. She could still run away if she lost her nerve in the face of this horror, but her protective instincts are so great that she stays and fights. It just felt like the tipping point a bit. I did the same thing with “Thingol and Melian,” where they hadn’t yet sealed their relationship by clasping hands so it is still up in the air. A bit more dramatic tension, I suppose.

See, I hadn’t thought about that—Elwë seems to fall so fast and hard for Melian that it’s easy to forget how much time really goes by in their meeting, technically. Years, in fact, maybe far more once they actually join hands. And then, of course, it’s after this meeting that he goes by the name Thingol. Because renaming is what Elves do.

All right, now for some easy lightning round questions. Regardless of the subjects of your own illustrations, who is…

Your favorite Elf of the First Age?

Kip: There would be many. Fingolfin fought Morgoth! Fingon rescued Maedhros. Turgon built that city. Eärendil brought on the War of Wrath. Idril was just such a great maternal figure. I love Beleg also. But probably the favorite is Finrod, who just knew he was going to die but had to honor his oath.

I only let you rattle off multiple answers because you did conclude with the greatest Elf of all ages of the world. Finrod for the win! Not only did he have Beren’s back, he also made first contact with Men and arguably ensured the Edain, and thereby the Dúnedain, would come to pass. If any other Beleriand Elf had encountered Men first, especially one of the sons of Fëanor, the story might have been very different.

Favorite mortal man or woman of the First or Second Age?

Kip: Tuor, but Húrin comes in a close second.

Favorite minion or monster of Morgoth?

Kip: Ancalagon. Sooooo huge.

A Dwarf you wish we knew much more about?

Kip: Durin the Deathless, the original.

A.K.A. Aulë’s very first stab at a creature of his own. The prototype. But yeah, Durin’s cool.

One more question. You’re an experienced parent and a therapist and a lifelong Tolkien fan. How could one get a child—say, a 5-year-old—well on his way to becoming a solid Tolkien reader without one coming on too strong? Asking for a friend.

Kip: That’s the question a great parent asks. Seriously.

Pair the experiences with Tolkien with some good times with you. I watched Fellowship with my son when he was five and it didn’t seem so scary for him. I watched it after we made brownies together, then watched Wallace & Gromit afterward. He still considers it the most cherished memory of his childhood. Not sure you want to introduce him to the books using the movies, but if he feels a closeness to you, he will naturally have an affinity for Tolkien. Be the good parent you seem to be and have the material around and he will most likely start to love it. Read The Hobbit to him for his bedtime story over the course of weeks. You both are probably in for a treat. I talk about it all the time with my grown son. Good luck!

Thanks! And thanks for giving your time and sharing your work. Folks should check our your website—and whaaaat, you can get a phone case with your art on it?

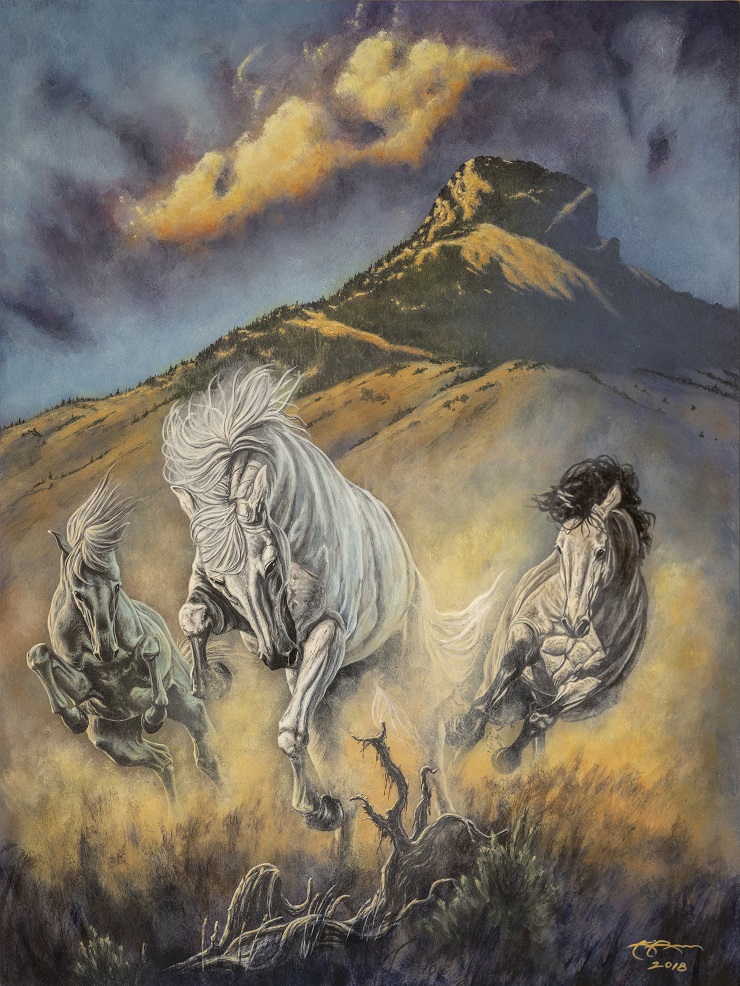

I’d like to end by displaying one more recent piece of yours. For all your Silmarillion pieces, you’ve still clearly got a few Third Age-related soft spots, like this one. What made you depict the animal that the “horses of the Nine cannot vie with,” who is “tireless, swift as the flowing wind,” and whose “coat glistens like silver” and by night “is like a shadow”? Seriously, Tolkien gives Shadowfax more of a physical description than Legolas!

Kip: As we all know, there are many astonishing scenes that beg depicting in Tolkien’s work. I have a queue that is literally hundreds of images long. So, if enough fans at conventions ask for a certain image, I move it up the list. People love their gods, Elves, and dragons, but horse lovers are very passionate. And I love painting horses. Challenging but dynamic. The Shadowfax painting came together better than most for some reason.

It’s also a wonderful moment of peace, even though it’s bursting with energy and force. This is Shadowfax, chief of the Mearas, at play.

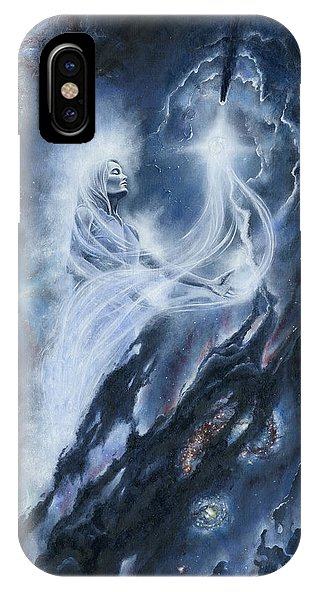

Top image from “Varda of the Stars” by Kip Rasmussen.

Jeff LaSala, who’s personally responsible for The Silmarillion Primer, will now hold Kip Rasmussen personally responsible for his own son growing up right. Tolkien geekdom aside, Jeff wrote a Scribe Award–nominated D&D novel, produced some cyberpunk stories, and now works for Tor Books. He sometimes flits about on Twitter.

Jeff – this is a wonderful interview. Thank you!! Really appreciated reading Kip’s responses and finding out a bit more about him. And now I’m tempted to spend far too long browsing his gallery. Truly a most talented artist.

I’m also a bit bummed out that I own neither an iPhone or a Galaxy! But quite tempted by the prints.

This was a lovely interview–thank you for sharing! And for sharing his stunning art.

On the topic of music… I love Hildegard Von Bingen! Also, are you familiar with Eurielle? Here’s a link to her Luthien’s lament, which is so pretty. Such a soaring voice.

Did you see the late Angus MacBride’s take on the Eowyn / Witch-king fight?

I second the advice of reading “The Hobbit” to one’s child as a bedtime story. My son is almost 17 now, but we did that back when he was around 7 or 8. I think I tried when he was a little younger and he bounced off it on the first attempt. At some point they’re too young to graduate from Boxcar Children to Tolkien. Be patient and wait until he or she enjoys it.

But the second, later go went great and over the next many months we finished “The Hobbit” and went all the way through “The Lord of the Rings” as well. Best bed times ever.

I also learned some things I had not noticed about Tolkien’s voice in “The Lord of the Rings” by reading it aloud. It seems like “The Two Towers” has a different voice/style from the first and last volumes. The language he uses is more what I think of as faux-biblical. Whereas the first and last volumes are more standard narrative.

Then as the movies came out — well I don’t know how many times I’ve seen the battle scene at Helm’s Deep now…

Just joined Tor, and thoroughly enjoyed reading your interview first. Thank you for sharing all the different forms to enjoy Tolkien’s work- I have sadly not heard of many of the composers, singers or painters mentioned in the article. Just spent quite a while discovering them all- a very nice wat to spend time recuperating- thank you.

I also found all the ‘name dropping’ a little intimidating, as I only read “The Silmarillion” once. Needless to say, I’m off to see if my library has a digital copy to borrow- need to read it NOW! ~especially after browsing thru Kip’s gallery of his stunning artwork, illustrations to put to the words.

Again, thank you for a very enjoyable, informative article.

Yes, thalessa, you should go and read The Silmarillion again. If you can handle the wordcount, I of course also encourage you to check out the Silmarillion Primer. Could make your second reading easier? :)

This was a really great interview, and I also enjoyed hearing about his perspective on child rearing. I’d definitely love to just have a cup of coffee and talk about the Silmarillion and Middle Earth with this guy :)

I really, really love the picture of Thingol and Melian – I really like how it’s the moment just before it all happens. There’s a kind of tension there, like it’s on the cusp of something world changing (which of course it is).

I read the Hobbit ot my son when he was maybe 5 or so. He enjoyed it quite a bit. LotR was still a bit much to him, but we went to New Zealand this past Christmas and so a few weeks before I introduced him to the Lord of the Rings movies. He’s 7 and into similar things (he loves stuff like Minecraft and watches a view ‘epic’ anime shows, etc) and he just LOVED it. I was worried it might be a bit too long for him, but it got really invested in the whole thing. He took Frodo’s claiming of the Ring for his own especially hard, actually. He also is very strongly of the opinion that the movie should end when Frodo awakens in Minas Tirith surrounded by his friends, becuase that is when everybody is together and happy. I don’t think he ‘quite’ gets what the ending is all about, but he apparently gets it enough to realize it’s bittersweet. I hope it continues to be a lifelong love for him that can grow with him as it has for me.

Okay, I just have to jump back over here to share Kip’s latest piece: “Olórin in the Gardens of Lórien.”

Or maybe, back in the Gardens. Back out of incarnate form, but perhaps reminiscent of his Gandalf/Mithrandir form.

I’m a long time late here, but all the same, wanted to say thanks for this interview, and thanks for the whole Silmarillion Primer series which I joined when it was almost finished and it gave me some very interesting reading during a difficult time. Posting here because it all your fault (in a happy way) that I ended up with Kip’s wonderful Varda of the Stars on the wall overlooking me now. I just kept going back to it, and looking some more, and eventually took the plunge. I’ve not often had the experience of ‘it just called out to me’ but I guess this was one of those times. For anyone else wondering, Kip was a pleasure to deal with when buying the painting, even with all the fun of international delivery.

Tim, thanks for stopping in to say this. It gladdens my heart. I’m jealous. I would have trouble choosing which to have a print of, if I had to choose…

And yeah, Kip’s such an easygoing chap!